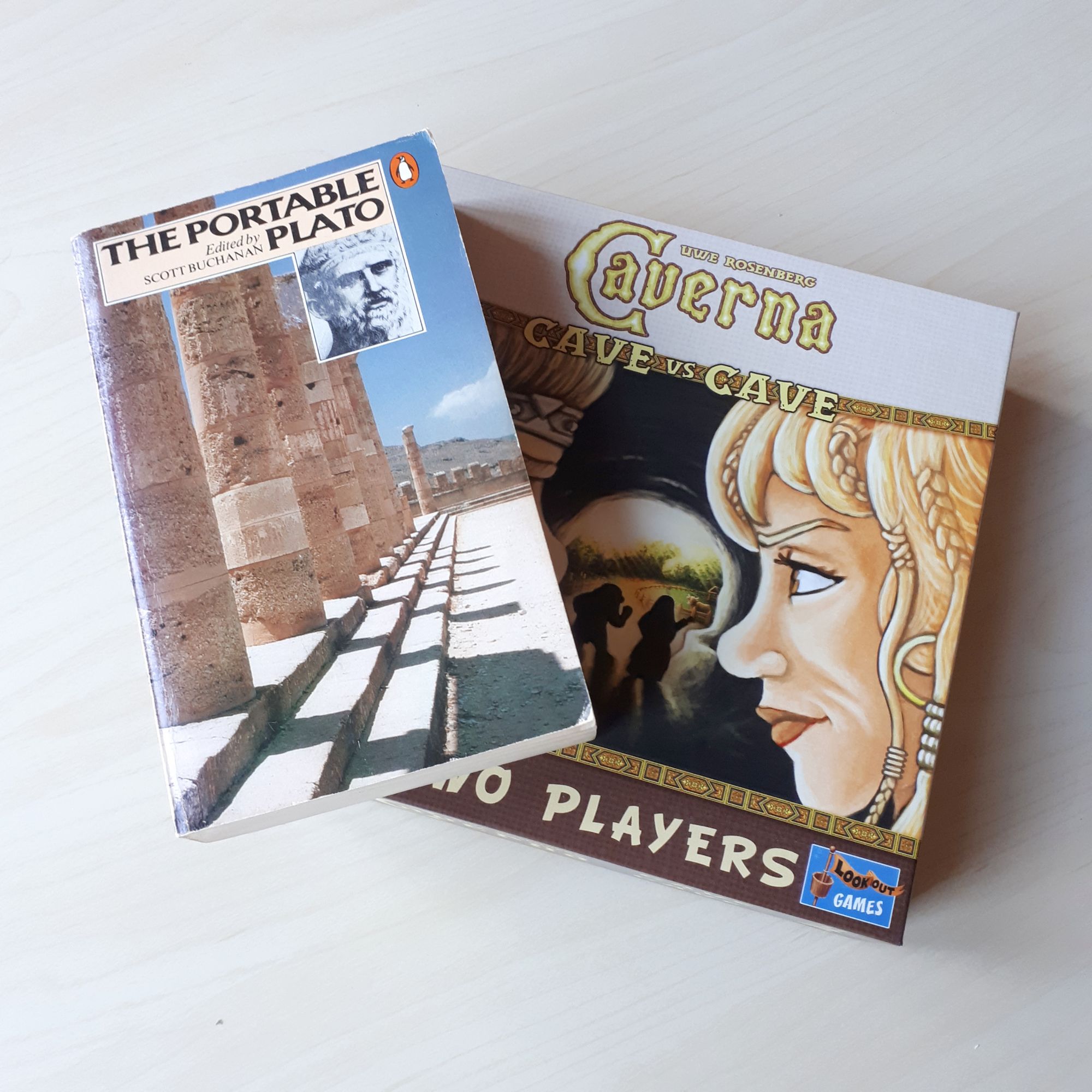

Cave vs Cave vs Cave Allegory: Using Plato to Play Boardgames

In his cave allegory, the Greek philosopher Plato describes people watching shadows moving across the back wall of a cave before being released and dragged outside into the sunlight. It's a parable about the very nature of Being and truth. In Caverna: Cave vs Cave, the German game designer Uwe Rosenberg has produced a boardgame in which players take on the roles of dwarf tribes seeking to excavate caves and triumph over their rivals. It’s a fun way to pass an hour.

Can reading Plato’s philosophical allegory help you to play Rosenberg’s worker placement game? In the first article in my new Board of Philosophy series I try to answer this question.

Caverna vs Cave vs Cave

Before I do, it is worth remarking that I will only be considering the slimmed down, two player version of Caverna called Cave vs Cave, first published by Lookout Games in 2017. This is because, unlike the larger game from which it is derived, Cave vs Cave focuses almost exclusively on the cave itself. Whilst the outside world is implied in some of the action tiles – for instance, Expedition and Cultivation – that world remains resolutely ‘off board’ and outside of the game, even if you play with the new ‘Era II’ expansion.

Cave Trajectories:

It is important to recognise the different trajectories involved in Plato’s and Rosenberg’s cave narratives. For the philosopher, the movement is outwards towards the entrance, where the ‘cave dwellers’ are thrust into the light and truth. For the game designer, the movement is inwards towards the back wall, where the ‘cave-farmers’ reach a natural limit to their excavations. In the first case, when the prisoner reaches the end of his allegorical journey he reaches the outside world, which stands for the world of ideas. In the second, when the industrious dwarf finishes his mining all he finds is more cave. If a player furnishes their entire cave with room tiles they are rewarded with an ‘Additional Cavern’ tile, which acts as a mere continuation. For the dwarf there is only ever more cave.

These different directions of travel are significant. After all, for Plato the prisoners’ movement is nothing less than one from a state of limited knowledge, where shadows are taken for beings, to one where they experience not just beings themselves but truth and ideas.

When read through the framework of Plato’s text, Rosenberg’s dwarves are actively retreating from the light of truth and are returning to a space of incomplete knowledge. Or, perhaps, they want to create a space in which others can be bound in ignorance (see below). In any case, their journey underground is not like that of the freed prisoner who returns to his former position at the end of the philosopher’s allegory as their return is not a simple walk and is far from guaranteed, but instead involves active work.

Recreating Plato’s Cave:

The geography of Plato’s allegorical cave is distinct and highly unusual. This begs a simple question: is it possible to recreate this strange geography in Rosenberg’s Cave vs Cave? The answer is… after a fashion. However, it’s not simple to do so.

Firstly, let’s summarise the geography of Plato’s cave. At its very rear are a group of individuals who are chained in place. Fixed there in this way, they watch the shadows passing by on the rear wall and attribute the voices they can hear to them. Behind them – which is to say one stage nearer the cave entrance – there is a small wall on the other side of which various people are moving and talking, carrying objects as they go. It’s the shadows of these individuals and their cargo that the prisoners can see. The shadows are being cast by the light from a fire that is nearer to the entrance again. Beyond the fire there is the cave mouth itself, and the outside world of the sun, moon and stars.

To summarise, Plato fills his cave with the following things (moving from back to front):

- a back wall on which shadows pass

- chained prisoners watching the shadows

- a small wall

- people walking past carrying objects

- a fire

- the cave entrance.

Cave vs Cave doesn’t have room tiles that exactly correspond to these spaces. Nevertheless, it is possible to furnish your cave in a way that mimics them.

The space occupied by the chained prisoners in the allegory can be represented in game by the Dungeon tile. This must be placed at the back of the cave if it is to correspond most closely with Plato’s scenario. Alternatively, you could use the Secret Chamber tile as it ostensibly operates in the same way and requires the same wall configurations. However, the Dungeon tile is the preferred option. Once built, the front wall of the dungeon will then need to be razed so that the shadows cast by the light further out in the cave can be cast onto the dungeon’s back wall.

There's no equivalent to Agricola’s Hearth or Fireplace cards in Cave vs Cave so it's not possible to directly replicate Plato’s fire on your player board. (In the full version of Caverna there is a Cooking Cave tile.) The nearest equivalent is the Bakehouse room. I think it's safe to assume that there’s a fire in the bread oven. This will create the light that is required to cast the shadows back into the dungeon.

Between the Bakehouse (standing for Plato’s fire) and the Dungeon containing the chained prisoners it is necessary to have a wall. This is the easiest part of the allegory’s geography to recreate in game. This is because the Bakehouse room has a very specific wall requirement. In order to furnish your cave with this room you need to have three walls in place, one of which can simply be positioned on the side that faces the dungeon. For our purposes, we can simply assume that this wall is a little lower than the others, so that the light from the oven can cast the shadows of the dwarves working in the Bakehouse onto the wall at the back of the Dungeon. For added flavour, we could even build the Shelf in the space between the two other rooms, although given the requirement that this be built on a single wall it would require a more complicated sequence of player actions.

Is recreating Plato’s cave in Cave vs Cave a viable game strategy? Not really. Whilst it’s possible to achieve it does depend upon you taking a very specific chain of actions, which in turn depends upon your opponent not doing them. It's also reliant upon the right room tiles being available and you having the materials to pay their cost. The Dungeon alone costs three stone and four gold to build and requires four walls to be in place, which means building a minimum of one but more likely two.

For all its difficulty, Plato’s cave would at least score reasonably well. The Dungeon is worth 11 victory points and generates gold when building a wall on future turns (which will come into play when, in this strategy, you go on to build the Bakehouse). Furthermore, the Dungeon is the second highest scoring tile in the game and so is good in the event of a tie (it can only be beaten by the State Room). Similarly, the Bakehouse is worth a further six points and again provides a way of getting gold.

Platonic Strategies:

Ultimately, then, Plato's philosophical text offers a way of responding to and thinking about Rosenberg's game board. Likewise, the game space becomes a way of dramatising the philosophical allegory. However, the interactions between the text and game are limited from the perspective of a game-winning strategy.

© James Holden 2019