Hyrule Fields Forever: Nostalgia for Video Game Worlds

As a kid I used to love running around the playing field behind our street. I would kick a football about with friends, attempt to leap over the muddy ditch and have other exciting adventures. As a twenty-something I used to love running around the field outside the village. Still a kid at heart, I would tumble about, speak to passers by and even ride my horse as I set off on quests.

Now, as a forty-something, I have a growing desire to see both places again, to run, ride and tumble around in them once more, for old time’s sake, and – who knows – maybe even have a few new adventures.

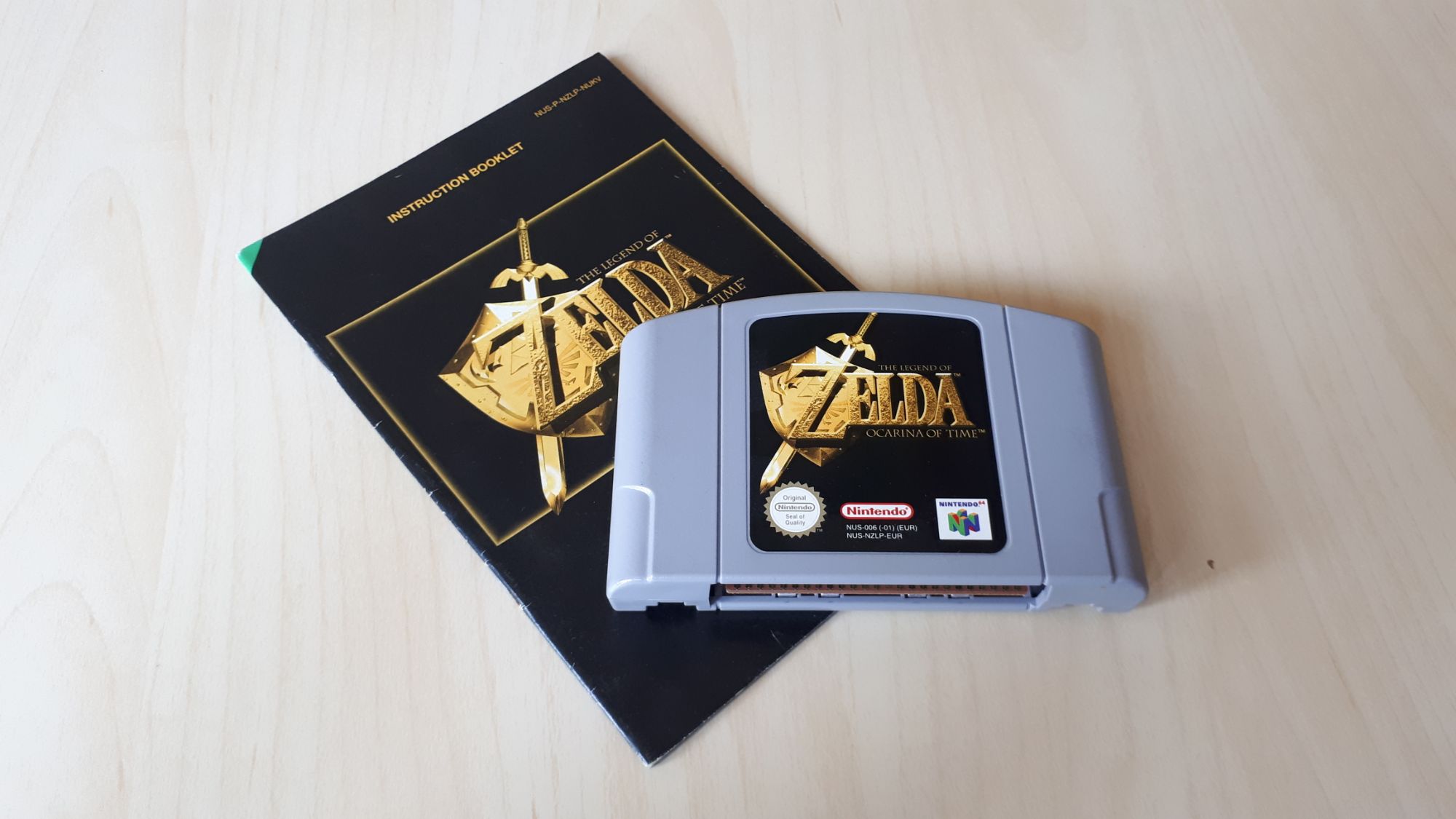

I’m unlikely to travel to the first any time soon as I’d have to take a five-hour drive back down the M1 – there are no fast travel points nearby. However, I can reach the second without leaving the house. All I’d need to do would be plug my old N64 back in because, rather than being a ‘real’ space, this other field is Hyrule Field in the video game world of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998)

It might seem strange to feel nostalgia for a place that only exists in an old video game. After all, I’ve never been there in any meaningful way. To put it simply, there’s no there to be in. And yet, despite this, I am nostalgic for this virtual game world. I find myself thinking back fondly to all those times I tumbled over the rolling green slopes, visited the ranch, and fought off terrible monsters all before running back to town before night fell and the bridge was raised.

The structure of my nostalgia for these two places – one real, one unreal – is the same. It's been so long now since I visited the field behind our street that my memories of the adventures I had there are now no more real to me than my virtual adventures in Hyrule. But what would I find if I did actually return to these fields?

The playing field would no doubt look a little different. Maybe the ditch I spent my afternoons jumping has been filled in. Perhaps the tree I swung from has been cut down. Such differences would be jarring. I could stand in the centre of the field and not find the place for which I was looking.

By contrast, the field in the centre of Hyrule would look exactly the same. Not a blade of grass would be out of place, not a flower replanted. What’s more, the very same adventures would await, perfectly preserved in the cartridge’s 32MB memory. I suspect that this unchanged vision would be more jarring than the changed sight of my old playing field. My own memory would not have been so exact in its preservation of the landscape and I would likely recoil at the differences between my recollection and the reality of the virtual reality displayed in front of me.

Like so many retro video games encountered again years later, what I once saw as a sprawling and colourful land would now appear foggy in its low 320 x 240 resolution, stretched across a flat screen for which it was never intended. It would also seem small, diminished not by my own increased size but by the immense open world games that are now the norm, not least The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017), a game with its own Hyrule Field.

Inevitably, my growing desire to visit both the field by my childhood home and the Hyrule Field of Ocarina of Time is also a desire to reconnect with the person I was when I first spent time in them – the young child playing football and the young adult sat in his student house playing his first expansive ‘open world’ game. Each of these places holds within itself a memory of those earlier versions of me, like a time capsule.

However, the risk is that by revisiting these locations and seeing them again that earlier saved version of myself would be overwritten.

© James Holden 2020